As much as love poetry, I must admit it’s often unapproachable. But it shouldn’t be! While it is true that poetry hides its wonderful meanings and hues for those who seek, effort shouldn’t be necessary to understand a poem — at least not in a basic way1. I will talk about two common issues I find in poetry, and tell you why and how to avoid them.

Ambiguity

I’ll say this plainly. Ambiguity is not a poetic value, it’s a tool. If you find yourself wondering, “what in the world do they mean?” when reading poetry, you’re not alone, and it’s likely that whatever you’re reading is too ambiguous.

Let’s first establish that poetry, as all art, has a purpose (if you disagree, fight me). Poetry’s purpose will differ depending on the poem and the poet, but on a basic level, poetry is a form of communication. So, effective communication is a poetic value. We can use this understanding to decide whether ambiguity would serve our goal of effective communication or not (because, remember, ambiguity is a tool).

If a poet — who we’ll call Clem — were to write,

The rose found divinity in a sea of nails

I would put into question whether he has something to say at all. The ambiguity here does nothing for the (fictitious) poem. It is an ineffective way to communicate whatever Clem wants to communicate. One solution against ambiguity is making the ambiguous line(s) more concrete.

It sounds like an obvious solution, but it’s a difficult one. A poet must make an intentional effort to concretize their poetry. It doesn’t “flow.” First, they must identify their line says nothing in particular, and then they must know what it is they actually want to say. It’s not always obvious what a poet means to say, even to the poet themself.

Take the line above as an example. Clem’s subject is a rose. The rose found divinity. What does that mean? What does the rose represent? The rose found divinity in a sea of nails. What is a sea of nails? These questions will help Clem concretize his line. First, the rose could represent a person. Maybe, though, the rose represents someone’s efforts to love. That’s more interesting. I would drop the rose metaphor and call it as it is, her love. Next, the efforts could be compared to divine love, hence the rose finding divinity. Still, it’s not clear what exactly about divinity it is being compared to. What about tragedy, a great tragedy? Perhaps that’s the sea of nails, nails that allude to Jesus.

Here’s how I would expand and concretize Clem’s line.

Her love was a tragedy beyond the crucified Jesus

for she could not resurrect herself

the sole victim of her passions

Why would you tell me the rose found divinity in a sea of nails when you could say this instead? What are you going on about? The new lines make the metaphors explicit, but that helps the reader understand what they mean. Take note that the concretized version, therefore, uses fewer metaphors than the original. Where the original used four (rose, divinity, sea, nails), the concretized only uses one (Jesus’ tragedy). In this way, less is more. Yet more is also more! The concretized version uses three lines rather than one because it expands on the metaphor. This does wonders for the reading experience.

Still, there are some ambiguities left to solve. Why is she a victim of her passions? Or even more importantly, who is she? These are things the poet could leave open for the reader to interpret or go on to explore depending on what the poet’s goals are. Whatever the poet decides, the reader now has something to latch onto (perhaps they will think about it for a while or talk to a friend about it), and that’s the value of ambiguity. It prompts consideration.

Let me be clear. There is indeed space for ambiguity. After all, personal interpretations would be impossible without it. Essays and Stories are better suited for unambiguous communication. Poetry must rely on what is not said, but ambiguity should never be a goal in itself

Complexity

I must tread carefully in making this point. Complex language can be evidence of skill and quality, yet it can very easily be evidence to the contrary. Complex language is neither a poetic value nor a tool. It is a byproduct of style. It is neither desirable nor undesirable, but it does make poetry more difficult to read. This is something we must consider when writing.

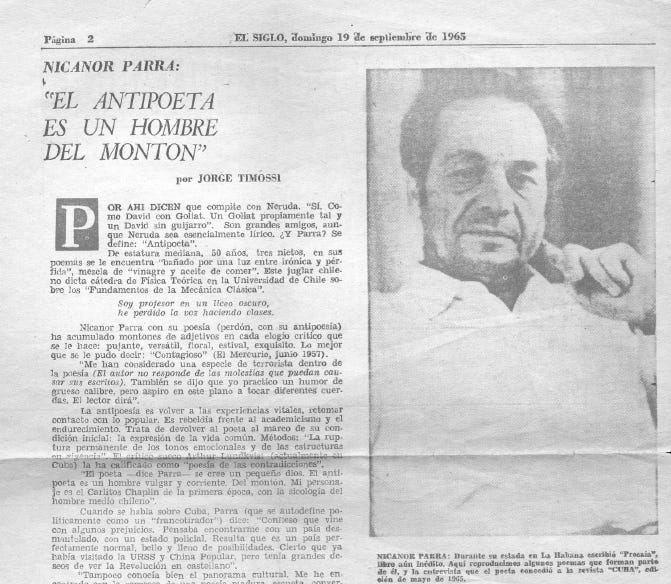

Let’s look at a poem by Nicanor Parra found in a digitalized newspaper published in 1965 (translated by yours truly.)

Poetries

Writing a poem

Is a forgivable foolishness

— You could find several apologies —

Putting it through a machine is a suspicious foolishness

But to print it

Is a thing without name

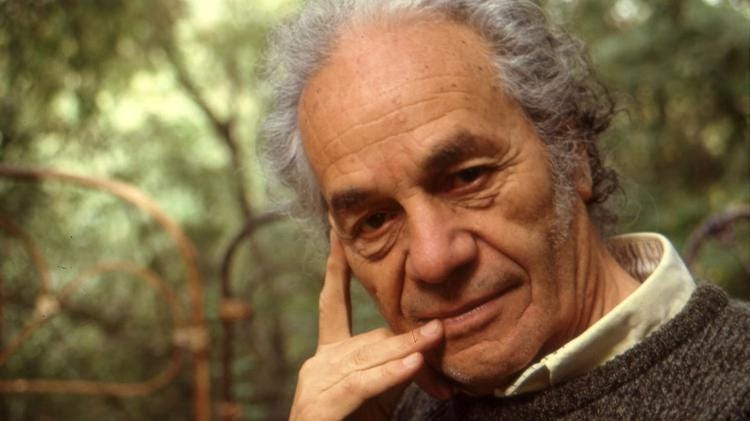

Could you think of a simpler way of saying this? I can’t! It’s clear and beautiful. Parra’s work is known for not being pompous, but rather straight forward and grounded. He actually wrote in such a different way to his contemporaries (from the 30’s onwards) that he revolutionized Latin American poetry, calling it anti-poetry!2 This is what good poetry is made of.

We English speakers are used to reading Shakespearean poetry in school. It’s good stuff, but it’s old stuff. It doesn’t come naturally to anyone anymore. Why should we aspire to sound like a 400 year old poet? Let’s be contemporary. Let’s be clear.

An Incipient Vision

I would like my work to inspire my generation to revisit poetry. I want to write poetry that is plain and understandable. I haven’t always written this way, and in a bit you’ll read an example (although paradoxically, I do like it). If the poetic element isn’t found in ambiguity or complexity, then where is it? That’s what I hope to discover: the poetic elements that transcend theatrics.

Here’s the exact opposite of what I want to do with my poetry. It’s the fruit of misplaced aspirations. Thank you for reading, and I look forward to seeing you next week!

Two books and their Souls

Mute, neither moved, like seated statues

Except for a finger advancing an adventure

Or an arm and hand on a quest for a sip

Then a head led the way, and turned to the otherLooking around, it saw two half-full glasses

Two book markers, two books, and their souls.

Two souls deep entranced by wood and ink

In two worlds set apart by a center tableAll it took was a sigh to break the spell

Then two eyes and a smile met a gaze

So two souls met again in their world

Set apart by a center table

Ofc, there are poems that break this axiom.

This is a gross oversimplification of antipoetry